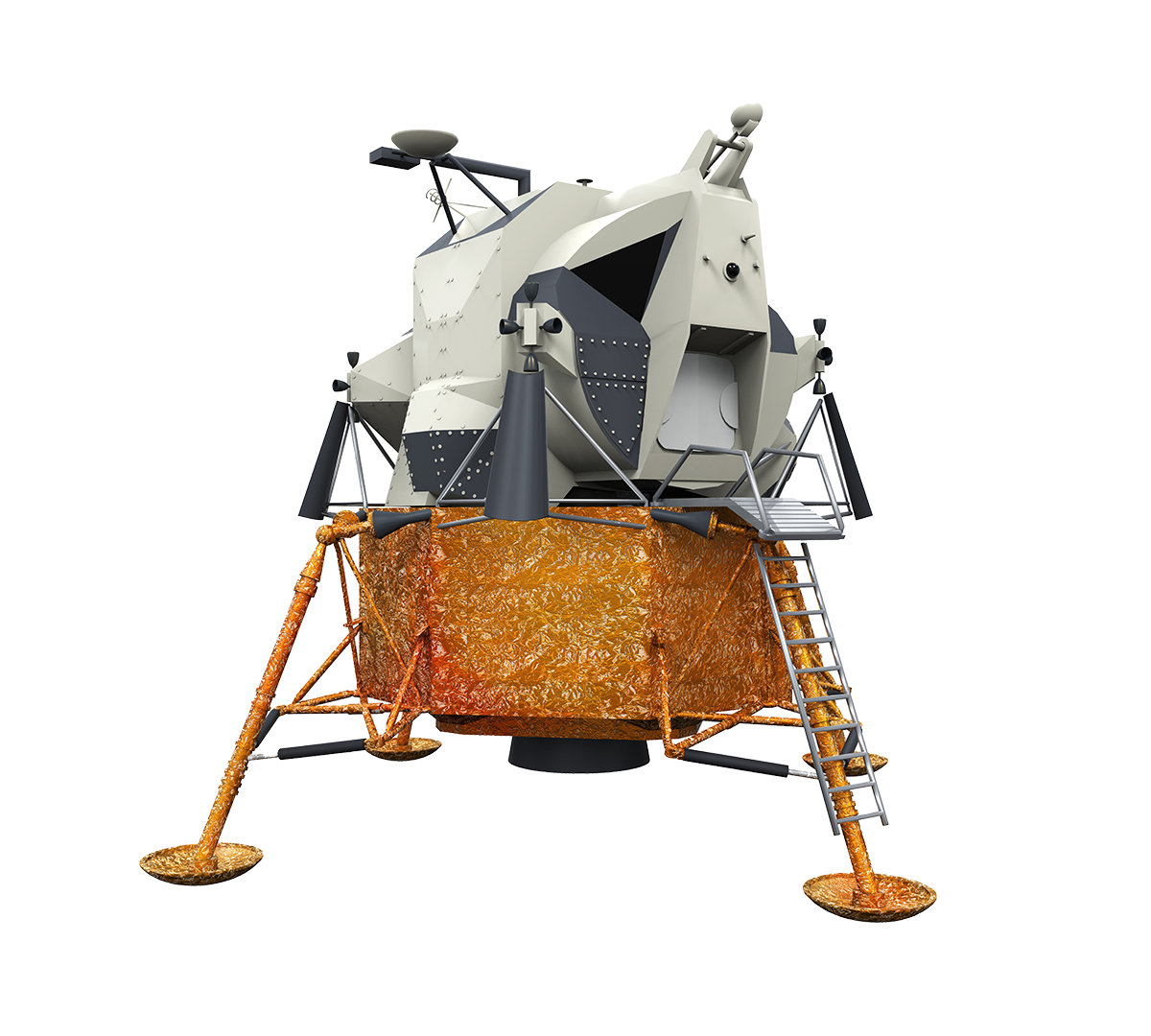

Photo Credit: NASA

As we approach the lift-off of our Alan Shepard anniversary countdown, we can’t help but spotlight the person who stole the show from the United States in 1961.

Imagine preparing to discover something for the first time. Something no one else has ever seen before. Something not only important to you, but to millions of other people too. The government is counting on you to make them look good and along with that pressure you are racing someone else in search of the same thing.

As Yuri Gagarin safely parachuted out of the Vostok 1 spacecraft, he became the most famous man in the world. Whether the United States liked it or not, the USSR had put the first person in space.

Gagarin was the Soviet Union’s hero. However, the 27-year-old Soviet Air Force test pilot wasn’t always amid fame and success.

Space historian and stellar Higher Orbits supporter, Francis French, led a webinar for our Space at Home History kit on the anniversary of Gagarin’s flight. In this webinar French detailed Gagarin’s childhood and the challenges he faced leading up to the day of his Soviet Space Program selection.

According to French, Gagarin fought his way out of his poor farming village that had been ravaged by Nazis in WWII. The town lost everything of value such as schooling, animals, and crops. Eventually, Gagarin’s siblings were taken too.

After the Nazis were pushed back, and the village was able to begin rebuilding, Gagarin eventually left the village to pursue opportunities in the city. His start as a foundryman led him to a flight school near his job.

“…but then, one of those things happens… that little moment in life where something goes well,” explained French, the author of Into that Silent Sea. “Right place, right time, or just making a choice that puts your life in a different direction.”

French explained how Gagarin began giving flight a try, and eventually ended up as a jet pilot for the Soviet Air Force. While Gagarin was stationed out of Luostari air base, he was approached by officials who were recruiting talented, young fighter jet pilots for a top-secret program, which he later learned was the Soviet Space Program.

After a long training process, it was decided that Gagarin would be the one that the Soviet Union would send to space.

It wasn’t just Gagarin’s flight skills that landed him this opportunity. As propaganda played a huge role in the Cold War, Gagarin’s personality, image and background also helped him become the leading candidate for the flight.

“In communist Russia, they really like the fact that Gagarin was the son of a working-class farmer; it made it seem like in the Soviet Union you could rise from the most humble beginnings and go on to do the most amazing things,” said French.

Following Gagarin’s famous flight in 1961, the United States graciously congratulated the Soviet Union on Gagarin’s success, but much more was brewing below the surface.

As French explained in an exclusive interview with Higher Orbits on April 19, the U.S. had been preparing for the possibility that the USSR would put a man in space first.

When news broke of Gagarin’s success, it reignited the importance of Shepard’s mission. Now there was more pressure politically due to the fear that Shepard would fail. French explained that the public relations around Shepard’s mission was handled more cautiously as the U.S. did not want to embarrass itself. They did not want to announce their plans to make it to the moon had Shepard failed.

“There were advisors in the White house who weren’t necessarily knowledgeable about the space program. They were just science people; they were going ‘maybe we should hold off, maybe we should do more un-crewed tests before we send a person. We want to be absolutely sure.’ Well, we could spend decades doing that. We got to take the risk at some point,” said French.

I asked French if this newfound pressure and tone made Shepard nervous. Not only was his mission important politically, but now White house advisors were casting doubts over the mission and Shepard’s safety.

And how did Alan Shepard feel?

Who better to know the answer than Dee O’Hara, the first aerospace nurse to work with NASA’s first set of astronauts.

“Alan rarely, if ever, showed any hint of nerves. A man of steel, so to speak. Much of this stems from him being very, very smart and putting in long hours of training. He showed "overconfidence" more than not,” said O’Hara in an email correspondence on April 21.

“And yes, he was very upset about Gagarin being first. John G was also.”