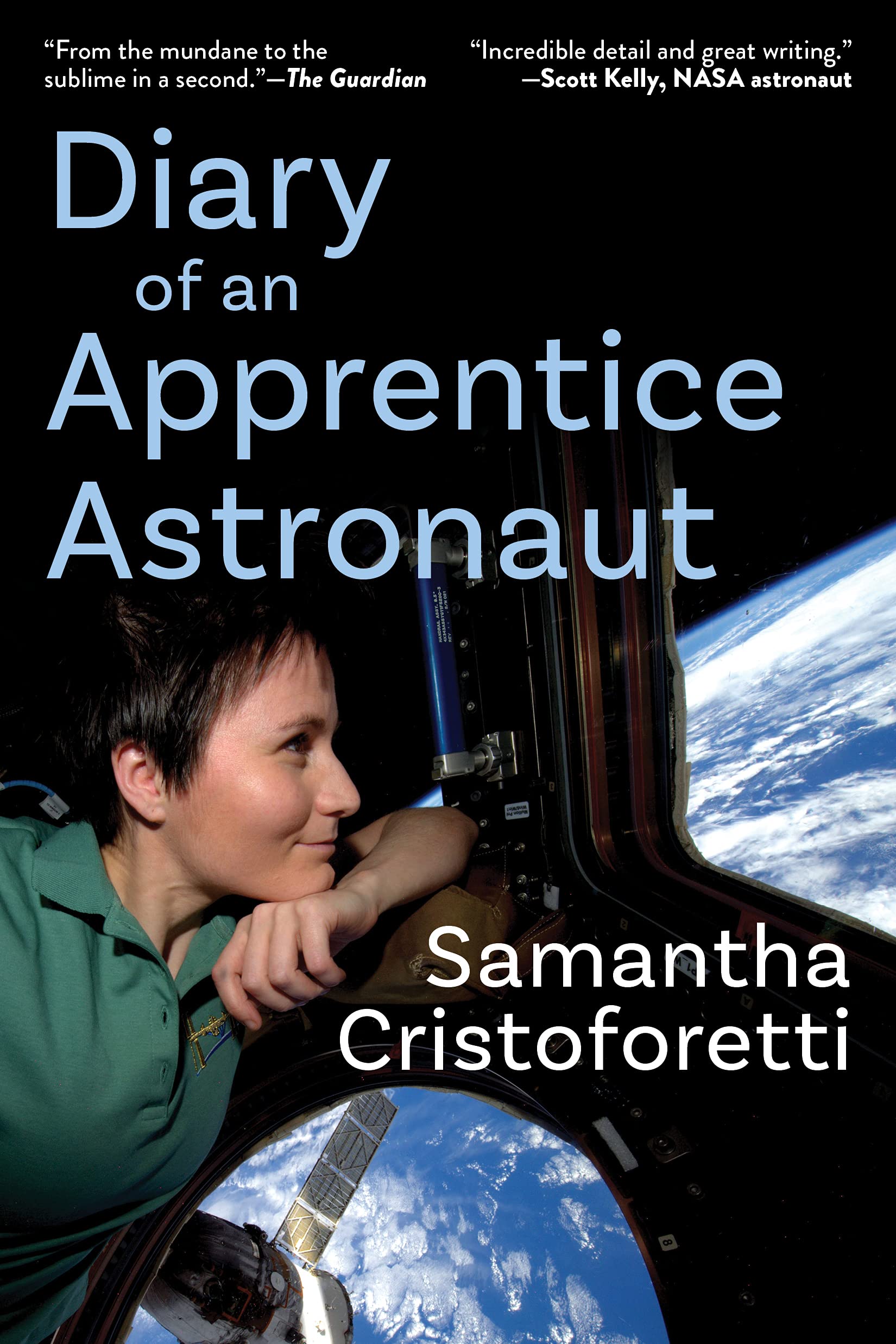

My first impression of this book was – warmth. Italian astronaut and recent space station inhabitant Samantha Cristoforetti wants to concentrate on the positives. And while it’s hard to tell if it is due to the book being originally written in Italian, or a pungent, sense-heavy writing style, the book is vivid with descriptions of color, of movement, of feeling. Who else has ever evoked Caravaggio when describing the light and shade of a space shuttle launch? Quoted Virginia Woolf when talking about space experiences? Or described their last few days before leaving Earth as if scenes painted in a church fresco? We’re along with her for the ride. We live in space with her.

She expertly captures little moments such as the odd tinge of loss when a small-scale project becomes larger, more public, and has to be shared with the world. Her description of how happiness can spread through the body is one of the best I have ready in any literary genre. Instead of relief when her training is over and her flight approaches, she shares a whispery pang of regret that years of regimen are about to end. We’re caught up with her as, one by one, she describes the last time she will do everyday things before leaving Earth; even though we know she’ll survive the mission, she expertly manages the reader’s tension. Hers is an emotional journey, in that every feeling Cristoforetti experiences as she moves forward in her career is described. But it’s not uncontrolled emotion; these are the feelings that come from being a driven professional, elated to reach every goal. She has the tough writing job of being good at everything in life, but needing to describe it without sounding arrogant. She also has an incredible grasp of detail, capturing informative snippets of life events I would have forgotten a week later. She’s happy when learning something new, plus skilled at describing the happiness of a new sensation that brings her ever closer to a flight into space. And once in space, she relishes the clarity of a distraction-free, scheduled existence.

I gained a real sense of how, during training, even during times of relaxation, Cristoforetti had a constant sense that she was being measured, judged, evaluated. Nothing was ever a guarantee, even when she was assigned to a flight, and she could never fully let her guard down. Any “free” time was best spent studying harder, to gain an extra advantage. She actually slept better in space because finally, she relates, she wasn’t bouncing around different time zones while training. It’s quite a career to pick. The discipline reminds me of an athlete training for the Olympics. Push too much, you might break something. Push too little, you won’t peak at the right moment. It sounds relentless, and suitable only for a very specific type of person. Fortuitously, she’s the right kind of person, who pushed harder to gain experience in tasks she might never carry out in space, rather than shy away from them. We learn how Cristoforetti would rather take on a task that risked her own life than one where the lives of her crewmates would be in her hands. We see how moments that might irk other personality types – inadvertent elbow-jabs from colleagues in tight quarters, for example – are mentally dealt with in ways that actually enhance crew bonding.

Cristoforetti is still an active astronaut, and you can tell. When spacefarers retire, they tend to become more honest about whom they liked and disliked, and other little details that would not be wise to share when they are still work colleagues. As such, I never really gained a sense of what her fellow spacefarers and co-workers were like. They all seemed to combine into a

professional, cheery bunch with little difference in personalities. But perhaps that’s how she sees them in reality. And it worked in this book, which focuses on Cristoforetti’s own experiences as she travels from nation to nation training, attending meetings, and working with hundreds of people whose job is to test and to assist her.

I love a good spacefarer memoir. I wish every space traveler would write one. Yes, I know, I know, there are over 560 spacefarers now. But they are from over 40 different countries, from different generations, with different experiences. Yes, some of their stories are going to sound the same. But the differences intrigue, surprise, and delight. It struck me how long this multigenerational genre has been in existence when Cristoforetti mentioned she was four years old when the first space shuttle was launched – a flight that came two decades after the first human spaceflight. And yet, once she is in space, this book reminded me more of the memoirs of cosmonauts on Soviet space stations in the 1970s and 1980s than anything contemporary. There are common threads of surprise and wonder mixed with the mundane chores of life across generations.

So is this book different from other spacefarer memoirs? Yes. I was surprised that I was two-thirds of the way through the book before we got into space – but this seemed to mirror the immense amount of training that has to happen first. And Cristoforetti describes the space experience differently than others, as she transitions from highly-trained expert of Earth to clumsy new arrival in space. She’s not trying to explain a wider view of a space station and the program. Instead, you move with her from little area to area, feeling and learning as she did, moment by moment. Eventually, Earth life recedes until, for her, lying down on a bed is a faint and distant memory. Every part of her aches to remain in space on the day she leaves it. It’s visceral. It’s special.